Five Policy Disruptions that will Result from the Individual Ownership of Autonomous Vehicles

By Michael Cunningham

Vehicle manufacturers, tech platforms, and robotics companies are currently in a race to test their own respective fleets of autonomous vehicles, for purposes ranging from ride-sharing to autonomous trucking. But even as drivers post videos of themselves eating chicken sandwiches while their Tesla is on “Autopilot,” federal, state, and local laws that influence the individual ownership and dictate operation of autonomous vehicles are varied or nonexistent.

As vehicle manufacturers rapidly move toward selling Levels 2, 3, and 4 driverless cars to individual buyers, those manufacturers, policymakers, and insurance companies will need to enact strategies to keep motorists safe, and help them navigate the hazy universe of sharing the responsibility of operating their vehicles with an automated system. I spoke to Stan Caldwell, Executive Director of Carnegie Mellon’s Traffic21 Institute and Executive Director of the Mobility21 National University Transportation Center, to get insight into what changes we might expect as autonomous cars become the prevalent source of transportation for U.S. motorists. Here are five policy disruptions that could change our current perceptions of owning and operating a vehicle:

1. Auto insurance companies will insure vehicles rather than individuals.

Currently, the system for insuring vehicles in the U.S. is built upon driver error, or personal liability. But if human drivers are no longer operating vehicles, then who, or what, is liable in the case of an auto crash?

“Instead of having 200 million drivers in the United States as customers, you may just have a handful of customers, which are the manufacturers of the machines,” said Caldwell. “Especially if it’s more of a shared-use model.”

And if the vast majority of auto crashes in the future are caused by mechanical error rather than human error, insurance companies will adjust accordingly, shifting their business model from personal liability to product liability.

“The insurance companies may no longer insure the individual,” said Caldwell. “To this point, insurance companies have always protected against the error of an individual driver who is at fault in a crash. There has always been product liability associated with vehicles, but what automation essentially negates in the future is the need for personal auto insurance altogether.”

Stan Caldwell

Executive Director of Carnegie Mellon’s Traffic21 Institute and Executive Director of the Mobility21 National University Transportation Center

2. States will license vehicles rather than drivers. And drivers will be required to complete additional training if they want to be licensed to manually operate an autonomous vehicle.

Currently, there are no federal regulations for licensing drivers. Driver’s licenses are issued at the state level, based on individual state regulations. And states license individual drivers, not vehicles. The one exception to this regulatory model is California, which has its own emissions standards that vehicle manufacturers have to follow on the front end of production.

But as individuals begin to own autonomous vehicles with pedals and steering wheels, the balance of authority between a human driver and an autonomous vehicle becomes nebulous. And to clear up that uncertainty, states will require different levels of licensing for individuals who want to share driving responsibility with an automated vehicle, versus those who want to manually drive the vehicle in certain situations.

“When the majority of vehicles are autonomous, you will have to go through specific training to be a human driver,” said Caldwell. “Especially in what they call ‘automation Level 3 and 4,’ where you are sharing the authority between a human and an autonomous vehicle.

“We are already seeing people treat Teslas, which are categorized as automation Level 2, like Level 4 vehicles. So I think that states will change their licensing policy to further prevent some of the accidents that we’ve seen as a result of people operating those vehicles irresponsibly.”

[A police car] could slowly drive a car back all the way back to the police station, whether there is a human in it or not – kind of like a tractor beam.Stan Caldwell

3. Municipal police forces in smaller communities may significantly decrease the number of officers on duty…

Traffic tickets result in billions of dollars in municipal revenue throughout the U.S. each year. According to a National Motorists Association blog post, somewhere between 25 and 50 million tickets for moving violations are issued each year. Assuming an average ticket cost of $150, the total annual up-front municipal revenue from traffic tickets ranges from $3.75 billion to $7.5 billion.

But what happens to that ticket revenue when 95 percent of the vehicles on the road are autonomous, and they are faithfully following all of the traffic rules without error?

“In small municipal scenarios, you are really eliminating the need for this 24-hour, standby police force, because law enforcement officers will no longer be out there spending most of their time focusing on traffic enforcement,” said Caldwell. “And if you’re not focusing on traffic enforcement, there often aren’t enough other crimes happening out there to keep full-time police officers busy in smaller communities.”

4. ...but police officers will have greater control over “rogue” vehicles in situations where they do need to safely pull a vehicle over.

Currently, police officers are highly trained to use mechanical strategies—from spiking, to road blocks, to physically fishtailing vehicles—to stop runaway or dangerous vehicles when they have no other choice. But these decisions come with consequences related to liability, safety, and probable cause.

With autonomous vehicles, police officers may have the potential to use special overrides to put the vehicle into “platoon” mode – a technological state that already exists for driverless cars that are being tested in fleets today.

“’Platooning’ essentially creates virtual trains out of autonomous trucks or cars,” explained Caldwell. “It allows for a situation where you can go on the highway and have one car, either operated by a human or autonomously, control a convoy of autonomous vehicles behind it. And all of the drivers behind the lead car can go into sleep mode. This maximizes drafting, which subsequently improves fuel efficiency.”

Giving police officers the ability to platoon autonomous vehicles will enable them to safely control driverless vehicles being used for illegal purposes, such as trafficking drugs, humans, or materials meant to weaponize the vehicles for terrorist attacks.

“The police car could be in front or back and put the vehicle into a platoon mode, where everything the police car does, that rogue car does,” said Caldwell. “You could just slowly drive the car back all the way back to the police station, whether there is a human in it or not – kind of like a tractor beam.”

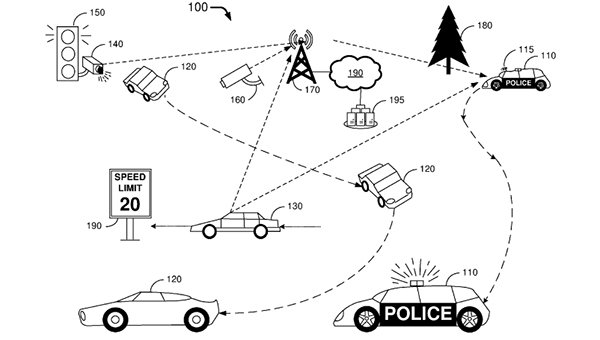

And if you think that this sounds more like something out of RoboCop than reality, think again. In January, Ford filed a patent for an autonomous police car.

License and Registration, Please

This is an illustration from Ford's January patent application, which describes technological innovations for building an autonomous police car. Image Credit: Ford Global Technologies, LLC.

5. Speed limits on highways will increase.

Currently, highway engineers design roadways for the safety of vehicles under the assumption that they are being driven by humans. But as autonomous vehicles nearly eliminate the possibility of human error, they subsequently increase the probability of safe operation at higher speeds on certain stretches of highway.

“It would become more of a matter of figuring out what a vehicle is designed to handle mechanically in terms of speeds based on a number of factors, including weather conditions,” said Caldwell.

Caldwell warns, though, that even on highways, as speed increases, fuel efficiency decreases. So it will be up to policymakers in different states to determine where the ideal threshold lies on different stretches of road.