Heinz College Students Target Weaknesses in Election Security

By Scottie Barsotti

A team of students examined historical election data in Allegheny County and determined that by compromising 10 percent of votes in Pennsylvania, an attacker could potentially change the result of more than two-thirds of statewide elections, including presidential elections.

Are American elections secure? In 2017, the Department of Homeland Security designated election equipment and processes as “critical infrastructure,” a change that allows greater federal resources to safeguard Federal, state and local elections. Foreign election interference and hacking have been in the news a lot in the last few years, shining a spotlight on the potential vulnerability of the U.S. electoral process to malicious actors.

But are these stories overblown? Or do we need to take election security risk much more seriously?

To bring some clarity to this issue, a group of Heinz College students from the Master of Science in Information Security Policy and Management (MSISPM) and Master of Science in Public Policy and Management (MSPPM) programs teamed up on a capstone project with VoteAllegheny, a non-partisan nonprofit that advocates for greater election integrity in Allegheny County (where CMU is located) and in Pennsylvania as a whole.

“This is a hot topic right now, and there are a lot of aspects involved, including data analytics, public policy, and technology that make it a complex issue,” said Will Cunha (MSISPM ’18).

The team analyzed local processes in Pennsylvania and Allegheny County, as well as state and county election data from 2000-2016, to determine how plausible certain types of attacks might be, and what steps can be taken to secure the vote.

Pennsylvania and Allegheny County were perfect case studies for this project (and not just because it’s our home state).

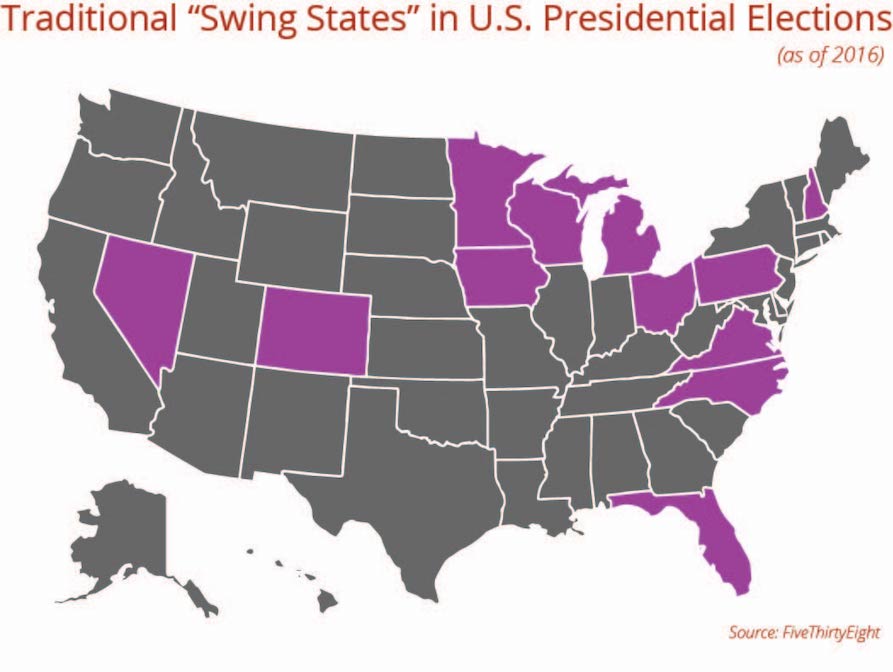

In statewide elections such as U.S. President, U.S. Senate, Governor, and Attorney General, the electorate in many U.S. states tend to lean strongly toward one major party or the other—these are often described as Republican “Red States” and Democratic “Blue States.” More competitive states, or “swing states,” are those in which statewide elections are much tighter from cycle to cycle, and party control is more elastic. Pennsylvania is one such state, which could make it an appealing target for a malicious actor.

“Pennsylvania is not only a swing state, but it is a state with many electoral votes which makes it very important in presidential elections,” said Salvador Ayala (MSPPM ’18). To emphasize that point, the team notes that in four of the five presidential elections since 2000, the outcome was decided by less than 10 percent of total votes.

“In the 2016 presidential race in Pennsylvania, there were only 44,292 votes between the first and second place candidates. That’s roughly 65 percent of the capacity of Heinz Field,” said Cunha, referring to the Pittsburgh Steelers’ stadium.

DETERMINING ELECTION RISK

The team used data analytics to determine the potential impact certain attacks might have on elections in Pennsylvania. By merely affecting two percent of votes cast, nine percent of statewide elections in Pennsylvania since 2000 could have been compromised in favor of the second place candidate. And if an attack could affect 10 percent of the vote, that jumps to 68 percent of elections compromised.

“We ran into an issue with trying to quantify the risk in election security. If you look at most risk management frameworks, many of them utilize a dollar amount as being associated with a level of risk,” said Cunha. “In the case of elections, we wouldn’t think of risk in terms of dollars lost, but rather ballots being changed or registrations being compromised.”

The highest risk to election security in Pennsylvania, according to the team, is the state’s online voter registration form.

In their research, they found a state database that includes voter names, addresses, precincts, political party, and voter participation history that can be purchased legally from the state for just 20 dollars. They argue that by using that publicly available data and merging it with stolen or leaked personal data found on the dark web, an attacker could change registrations by impersonating registered voters. When conducted against a targeted voter bloc—identified via social media trends or other data—the potential implications could be quite large.

Cunha notes that a lot of focus is placed on election equipment—specifically electronic voting machines—but that they are only one part of a complex process. And while hackers have shown an ability to crack voting machines (e.g. DEFCON’s Voting Village), the students thought it was unlikely that an attacker could actually compromise a large enough number of machines in enough key precincts to have a measurable impact. (Especially when a bad actor may be just as effective by simply making it appear as though an attack has taken place, sowing doubt in the result).

“There is a big difference between what is possible and what is practical,” he said. “Focusing just on election machines is not what we would recommend.”

Rather than replacing voting machines, the team suggests less costly measures in the short term, such as adding two-factor authentication to the registration system and fixing previously identified vulnerabilities in currently utilized voting equipment.

Moving forward, election data can help determine where to focus more targeted attention nationwide.

“We can use data analytics to determine what precincts, counties, and states are most at risk. That way we can allocate resources more optimally,” said Ayala.

Additionally, the students provided insight on the subject of internet voting.

[RELATED: See our previous story on e-voting]

“It sounds cool, and could potentially facilitate more people voting because they could do it on their phones. But what we’ve found is that moving toward less technology, like paper ballots, would be better. When anything is connected to the internet regardless of how much technology and security is applied to it, there will always be a vulnerability that is discovered or leveraged,” said Cunha.

This capstone project, entitled “Election Security in Allegheny County and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,” was completed by Will Cunha, M.J. Emanuel, Koji Ina, and Salvador Ayala.