Out of Touch, Out of Print: Professor Rebekah Fitzsimmons on Dr. Seuss and the Importance of Inclusive Storytelling

By Scottie Barsotti

On March 2, Dr. Seuss Enterprises announced they would cease publishing six Dr. Seuss titles, including:

- "And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street"

- "If I Ran the Zoo"

- "McElligot's Pool"

- "On Beyond Zebra!"

- "Scrambled Eggs Super!"

- "The Cat's Quizzer"

The announcement—which coincided with both Seuss’s birthday and the start of Read Across America—explicitly stated that the six titles would no longer be published because these books “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.” Seuss Enterprises further noted that the decision had been made over a year ago in consultation with experts and educators, stating that this kind of regular review “is only part of our commitment and our broader plan to ensure Dr. Seuss Enterprises’ catalog represents and supports all communities and families.”

The announcement garnered national attention, from send ups on late night TV to politicians decrying the move as an example of “cancel culture” on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives.

We spoke to Heinz College professor of professional communication and children’s literature expert Dr. Rebekah Fitzsimmons about the announcement and its cultural impact.

Heinz College: From a purely communications standpoint, what is the importance of inclusive communication?

Rebekah Fitzsimmons: I regularly teach our students here at Heinz College that communication is what moves ideas from amorphous concepts inside your brain to reality—if you can’t explain your theories or proposed policies to a wide variety of people, it’s unlikely they will ever be more than theories. Companies don’t buy products they don’t understand, and governments don’t fund initiatives that they can’t explain clearly to their constituents before election day.

Communication is fundamental to what makes us human, and telling stories is at the root of our ability to communicate clearly. I would argue that children’s literature shapes the way we learn the world around us, both in terms of oral and visual literacy as well as cultural cues, social norms, and morality lessons. Framed that way, taking a close look at the tradition of children’s literature in the U.S. and working to make it a more inclusive body of literature is vitally important.

HC: For someone who grew up with these books—what does it mean to them?

RF: There is a reason this issue is such a hot topic. There is an emotional connection to the books we read as kids.

I think many people fear that to recognize and admit that Seuss’s books have racist undertones is to be tainted by association. If I liked Seuss as a kid and Seuss is racist, then am I also racist? Or, even worse for some, if I let my kid read Seuss, does that mean I’m a bad parent and my kid is going to grow up to be a racist?

The level of nostalgia and emotional attachment to our childhood favorites often gets in the way of examining those texts with a critical eye.

The public call to diversify the overwhelmingly white world of children’s literature has been going on since at least 1965, but the growth of social media and an increasing focus on racial equity in the U.S. have helped push it to the forefront of conversations more recently. We’ve seen recent controversies over the legacies of other popular and much loved authors, like Laura Ingalls Wilder. As someone who loved her books as a kid, it was a painful experience to recognize that I had missed or glossed over the racist depictions of Indigenous and Black people throughout the Little House series. It was uncomfortable to further realize that had I not specifically chosen to study children’s literature in my graduate work, I might have passed those books on to the children in my life without reexamining that content. I can sympathize with folks who find themselves in similar situations; however, I think as a society, we need to work through that discomfort and take these conversations seriously.

HC: Some people might make the argument that these are children’s books and that they are harmless, or that kids don’t understand that these books are depicting something racist. In your opinion, why is that a flawed argument?

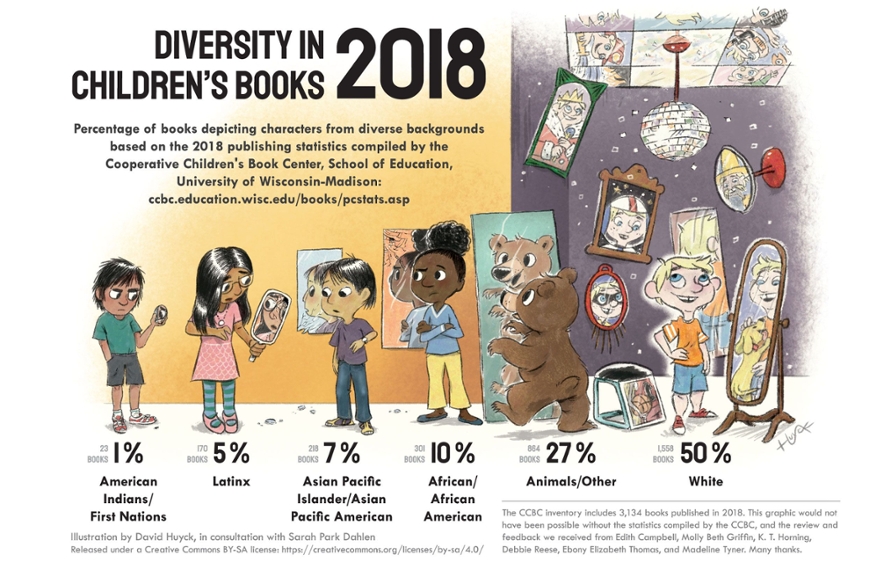

RF: When someone says “kids don’t notice” racist images, who are they imagining? For most people, they are picturing a white child as the reader of those children’s books. According to the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, the vast majority of children’s books feature white protagonists, so it is easy for white children to imagine themselves at the center of those stories.

However, this argument changes when you imagine the reader is an Asian child: now Seuss’s racist depictions of Asian characters with slanted eyes, conical hats, and subservient positioning creates a distorted reflection of that child’s identity (to borrow phrasing from Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop). Or imagine the reader is a Black child, who is looking at the images of Black characters with monkey-like bodies and exaggerated facial features reminiscent of minstrel shows.

Kids notice. Kids aren’t dumb. Kids are sponges; they soak up everything around them and draw conclusions. They pick up on things like gender roles, declaring “Pink is a girl color” or “only boys can be firefighters!” White kids notice when people who look different from them are portrayed in mocking caricatures or stereotypical roles.

Children want to see themselves reflected in the books that they read. Children of color are more likely to encounter books with inanimate objects as the protagonist than any protagonist of color. When there are no heroes who look like you and all the sideline characters who look like you are portrayed negatively, children notice. Children know and feel those racist images and the attitudes behind them. Racism in children’s books is harmful to everyone.

Beyond that, we have studies that show the effects of the relentless lack of representation and misrepresentation has on children of color and the harm it can do to children’s self-esteem and sense of identity. There are also growing examples on social media of the joy children experience when they finally see themselves reflected in books and media.

Representation in children’s books matters. For example, a quantitative study showed that professors in children’s literature are overwhelmingly portrayed as older white men; with that image reinforced over and over again, children will come to the conclusion that this is who can become a professor. Children as young as kindergarten, when asked to draw professionals like a scientist, a doctor, a teacher, and a nurse will draw white men as the doctors and scientists and women in the more care-oriented roles. This is why work like “This is What A Scientist Looks Like” has such power: changing the patterns that children see and observe in their literature and media helps shape their worldview and allows them to imagine themselves in a wider range of roles.

HC: Disney, Warner and other big media houses are still streaming content that contains cultural stereotypes, but with disclaimers. In the publishing/children’s lit context, why is this the right move to take these Dr. Seuss titles out of print instead of continuing with a disclaimer?

RF: Imagine I am browsing the cereal aisle. I come across a brand of cereal that I ate when I was a kid. I joyfully pick it up before I notice the disclaimer on the front that reads “This cereal has not changed its recipe since 1950; therefore, it contains a number of known carcinogens for historical accuracy.” With literally hundreds of other options laid out in front of me, I’m going to smile fondly at memories of eating that cereal, but then put it back on the shelf and choose a healthier option to take home to my family.

With so many great children’s books out there, I would imagine most parents would make the same decision if confronted with a warning label about racist imagery on the front of a picture book.

Of the six books that were discontinued by Seuss Enterprises, I suspect the decision to stop publishing most was a market-driven one. I study children’s literature professionally and have published on Seuss, and even I had to Google Scrambled Eggs Super! and McElligot’s Pool. Seuss had an extensive catalog of more than 60 books, and not all of them are top sellers like The Cat and the Hat or The Grinch Who Stole Christmas. I suspect most of the discontinued books were rarely being reprinted and were not in high demand already because they are so dated and problematic. The decision to cease publication will likely save Seuss Enterprises money in the long run. Adding a disclaimer to the front of a relatively obscure Seuss title likely would have had the same effect of radically curtailing the sales of these books, but with the upfront cost of printing and labeling the books for the publisher.

HC: Due to depictions in these books and other known problems in Dr. Seuss’s work, should parents and educators question the entire Seuss catalog?

RF: There are educators who are and have been questioning Seuss’s entire catalog for years, some of whom see the announcement from Seuss Enterprises as a half measure (largely because they also suspect these books were already not selling well, so ceasing publication has very little impact on the publisher’s bottom line).

Seuss had an extensively documented career as a political cartoonist that included a lot of incredibly racist imagery. In 2019, Katie Ishizuka and Ramón Stephens published a fantastic quantitative study of 50 of Seuss’s books that demonstrated the extent to which Seuss’s books overwhelmingly feature white (human) characters and the very few (2%) of characters who are not white are heavily racialized, stereotyped and dominated by white characters.

Philip Nel’s book Was the Cat in the Hat Black? documents the roots of Seuss’s iconic character in blackface and minstrelsy shows: the Cat’s appearance was reportedly based on Annie Williams, the Black woman who operated the elevator at Seuss’s publisher, Houghton Mifflin, including “Mrs. Williams’ white gloves, her sly smile, and her color.” While I do expect these conversations to continue, I don’t think we’ll see the end of The Cat in the Hat or Seuss any time soon.

HC: There is value in shared cultural experiences. For adults who’ve had these shared experiences/reference-points, that are now found to be harmful—does this provide an opportunity to create (purposefully) new shared cultural touchpoints?

RF: There is value in shared cultural experiences, but these shared cultural experiences also naturally evolve over time. For example, my grandparents loved the Rat Pack and I loved my grandparents. But when I tried to watch the original Ocean’s 11 with them after the [2001] remake came out, I didn’t understand any of the cultural references or jokes—the movie didn’t make sense to me. For my generation, Harry Potter was a massive phenomenon that swept through our collective experience and created an international cultural touchstone that unites us in a very specific moment. However, 50 years from now, it is entirely possible that my grandkids will find Harry Potter to be outdated and will prefer to read something else. No one is cancelling the Rat Pack or Harry Potter by choosing to consume media that better reflects the current moment.

While I do think Seuss will remain a cultural touchstone, I hope this conversation may help parents and educators explore other books or authors in order to find new texts to share. Culture evolves naturally over time. Books, movies, and TV shows that are considered classics by one generation fall out of circulation as they are replaced with new favorites. Curation is not the same thing as censorship; a publisher deciding that certain books published half a century ago no longer reflect the values of the current book market—and therefore are no longer worth re-printing—is not particularly remarkable. However, I do think the highly visible controversy around this particular set of books being discontinued speaks to the value of children’s literature. The books we share with our children matter.