Evidence-Based Approaches to Preventing Mass Shootings

By Elaine Vitone

From Buffalo to Uvalde, Tulsa to Chattanooga, America’s epidemic of mass shootings is at a boiling point. As lawmakers debate various approaches to preventing further violence, scholars engaged in the study of this alarming trend are pressing for action that is based in fact and enacted in service of the greater good.

In 2019, the National Science Foundation sponsored a workshop led by researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and George Mason University. The team of experts in criminology, psychology, statistics, and economics was tasked with identifying concrete steps to counter mass shootings in the United States and save lives. The following year, in the journal Criminology & Public Policy, the team published the following evidence-based recommendations:

- Restrict the most deadly components of firearms: large-capacity magazines, above all, as well as accessories that increase discharge rates.

- Instate universal background checks and other measures to keep firearms out of the hands of individuals who are a danger to others or themselves.

- Improve systems to detect and respond to threats, focusing on would-be shooters’ “leaked” intentions as well as spikes in gun-purchasing patterns.

- Support speedy medical treatment for mass-shooting victims through training, drills, and continuous evaluation of first responders’ effectiveness.

- Begin formally tracking mass-casualty incidents by creating a national data system.

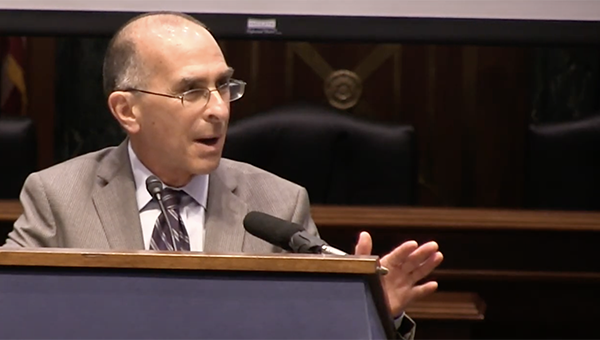

Recently, in the wake of the tragedies in New York State and Texas, we spoke with Daniel Nagin, acclaimed criminologist, Heinz College professor, and coauthor of these recommendations, about the unparalleled crisis of mass shootings in the US—and the resistance to enacting policy reform that could address it in a meaningful way.

Inaction from our policymakers will only result in the continuation of these horrific events.Professor Daniel Nagin

Mass violence is not a new phenomenon in this country, says Nagin. But it is accelerating, and will continue into the foreseeable future if nothing changes. As the workshop team noted in 2020, the vast stock of high-capacity firearms among the populace “will remain with us for generations.”

It is possible, however, to immediately begin to limit the harms of these attacks—if legislators take action now.

“There is no easy solution or quick fix for these horrific events,” Nagin says. “No one policy change will come close to solving this multifaceted problem. A comprehensive approach is required.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Heinz College: Is there a particular event that's commonly regarded as the point when this rising tide of mass shootings began? Perhaps Columbine?

Daniel Nagin: No. The usual definition of a mass shooting is an event in which four more people are killed. The ones we hear most about are those that occur in public places, where there's indiscriminate slaughter of people.

But there are also many in which family members and friends are killed. Those kinds of events have been going on for a long time.

As for racist motivated mass shootings as in Buffalo, it's important to keep in mind that the era of lynchings and Klan activity goes back to the late 19th century. Violent extremism is nothing new to the United States. I think sometimes that's forgotten.

Now, it is correct that there does seem to have been, in the last couple of decades, an acceleration of this problem, for reasons that are not well understood—though there is some indication on social media that there's a kind of a copycat behavior going on. But it's not as if Columbine was the beginning of this. Remember, there was a mass shooting at the University of Texas at Austin in 1966.

HC: In your view, why do mass shootings, on this scale and at this frequency, only happen in America?

DN: I think the explanation is simple: the overwhelming availability of firearms in the United States compared to other countries. That's the only credible explanation. Virtually all of these mass-killing events are with firearms.

Doing international comparisons of crime is difficult, because it's measured differently in different countries, but there's good reason to believe that crime rates are not materially different in the US versus, for example, Western Europe. The chances of your house being burglarized here are not materially different—and actually may even be lower here than they would be if you lived in Western Europe.

The exception is homicides which are at persistently higher rates in the US than other Western countries. If there's a conflict and you strike out with a gun, it's just more lethal than it would be with knives or your fists.

HC: What is your reaction to the claim that mass shootings are, fundamentally, a mental-health issue? Do the data support that?

DN: No. That's not a correct claim.

I think this framing conflates mass shootings with efforts in schools to try to identify children who are having a mental health crisis, and to try to intervene early to get the child back on track. There's much to be said for those efforts—but for reasons that have nothing to do with preventing mass shootings.

In reports about Senate negotiations, it sounds like support for [mental health programs in schools] might be on the table. But I would say that is unlikely to have any kind of material impact on mass shootings.

Though there are [outlier] cases like the one in Aurora, where the shooter did have a diagnosed mental health condition, in general they do not. This behavior is obviously disturbing. But being angry, having a grudge, and those kinds of things do not make a person mentally ill.

And it's important to keep in mind that many diagnosed mental illnesses, like anxiety and depression, are actually often associated with people being less aggressive, not more aggressive.

HC: What do you make of the fact that there is still no national database for tracking and studying mass shootings in the United States?

DN: Politics. For decades, there's been very little federal-level support for studying gun violence in general. It's only recently, with the Biden administration, that funding is now available. I can't help but believe [politics] have also affected data collection on the matter.

HC: In the two years since the report was published, what, if anything, has changed?

DN: Little has changed, unfortunately, even in the 10 years since Sandy Hook. There have been, predictably, more gun restrictions in blue states, and gun-rights expansions in red states. But there's been very little movement in taking measures that there's reason to think would serve to mitigate these problems in a substantial way. And the changes that at least are being negotiated by the Senate now are very, very narrow.

The most important recommendation in our report—which, unfortunately, has no political traction whatsoever at the moment—is to reduce magazine capacity. These high-capacity magazines have 20, 30 rounds. Shooters can discharge them very, very quickly, and with modifications they can discharge even faster.

An extreme example of this was the mass shooting in Dayton, Ohio. That shooter killed eight people in 32 seconds before he was killed by a cop.

HC: I understand you have a personal connection to Tree of Life here in Pittsburgh, the site of an antisemetic terrorist attack in 2018 that killed 11 people and wounded 6. Would you be comfortable sharing your reflections on how the community has been shaped by that mass shooting?

DN: I went to religious school at Tree of Life as a child. When I was in school, something like this was just utterly inconceivable. I mean, it was nothing that would even cross our minds.

When the mass shooting happened, I was in Zurich, Switzerland. I was taking a nap. I woke up and I turned on the news and there it was, this neighborhood that I know well.

I actually do research with a physician who was on duty in the emergency room and treated some of the people who were rushed there from Tree of Life. He said that the fact that they got them to treatment so quickly saved lives.

I think, unfortunately, these things are becoming so commonplace that in people's minds, the mass shooting at Tree of Life is probably fading away. Here we are, almost four years after it occurred, and the shooter still has yet to even be brought to trial, which to me is unfathomable.

But the impacts of each of these mass shootings are far beyond the people who are directly affected. There are children—who didn't go to Robb Elementary and don’t live in Uvalde, Texas—who are scared to go to school now. One would hope that finally there would be a willingness to come to grips with this problem.

Inaction from our policymakers will only result in the continuation of these horrific events.