Heinz College Students Putting Elections in Your Hands. Literally.

By Scottie Barsotti

When compared to technology advances elsewhere in American society, elections have stayed relatively “old school”—with good reason, according to many experts.

Innovations in electronic voting could streamline the voting process and boost civic engagement, but pose substantial security hurdles. Students at Heinz College have recently worked to understand this important and complex issue.

Turnout among eligible voters was estimated to be about 57.5 percent for the 2012 presidential election and only 36.4 percent for the 2014 midterm. Voting remotely from a computer or mobile device could make the franchise more accessible to many voters—citizens with disabilities and overseas voters, for example. But such an option may also improve domestic turnout, particularly among young voters. If secure, such a system could change the political landscape, not only for the U.S., but for other democratic nations and future democracies across the globe.

Addressing major problems in Internet voting security

A team of Heinz students in the Master of Science in Information Security Policy and Management (MSISPM) program recently collaborated with Oregon-based R&D firm Galois and the U.S. Vote Foundation on a report on Internet voting.

“There have been many [Internet voting] projects in other countries,” said Susan Dzieduszycka-Suinat, president and CEO of the U.S. Vote Foundation. “We wanted to do a U.S.-based research project which basically answered the question, ‘If we had to develop an Internet voting system for the U.S., how would we do it?’”

Among the team of experts contributing to the project, there was general consensus that the only acceptable system for an American election would be an end-to-end verifiable (E2E-V) voting system.

“The [Heinz] students were asked to do research on existing systems and to put together a competitive analysis,” said Dzieduszycka-Suinat, remarking that the students’ analysis was slotted into the final report on the topic. “[Their work] was very helpful and it showed us that the state of play in E2E-V systems is poor. It was extremely useful to have that contribution. It was something that we would never have had enough time for, and it gave great headway.”

The intent of the project was to research and lay the groundwork for a prototype E2E-V Internet voting system that could be both secure and scalable to national elections. The Heinz students found that current technologies were insufficient in fundamental ways—usability was a major area of deficiency—and could not meet the unique privacy and security demands of elections.

Heinz alumnus Ron Bandes (MSISPM ’10), president of VoteAllegheny and a cybersecurity expert for the Pennsylvania Joint State Government Commission Advisory Committee on Election Technology, says that where privacy is concerned, people often conflate e-commerce and voting transactions, though they are structured very differently.

“In fact, voting is a much more difficult security problem,” said Bandes. “With e-banking and e-commerce you have receipts, so you can prove the transaction. You can’t have a receipt in voting. You can have a receipt that says, ‘I voted.’ You cannot have a receipt that says, ‘This is how I voted,’ because of the possibilities of vote buying or coercion.”

The gold standard in elections for years has been paper ballots for their ability to be both verified and re-counted by hand. But many states have created processes by which voters can return ballots electronically. Only five—Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Missouri, and North Dakota—allow ballots to be returned via web portal. Alaska is the only state in which web-based voting is available to all eligible voters.

Many cybersecurity experts treat Internet voting as not only a technical challenge, but also a matter of national security. Recent hacks of the Democratic National Committee and several states’ voter databases have exacerbated those concerns.

MSISPM Program Director Randall Trzeciak advised the student team on the Galois project.

“There are risks associated with [online voting],” said Trzeciak. “If you ask any bank or financial institution, they write off a certain amount of fraud as a cost of doing business. There is, in my opinion, not an acceptable level of fraud that could occur in a voting process. We should have confidence that every vote would count as was intended.”

The students’ recommendations for the security system included robust validation of user credentials, an encrypted exchange of information from server to user and from user to database, and an audit capability that would give the voter confidence that their vote was both recorded as cast and counted in the official tally.

Driving voter engagement at home and abroad

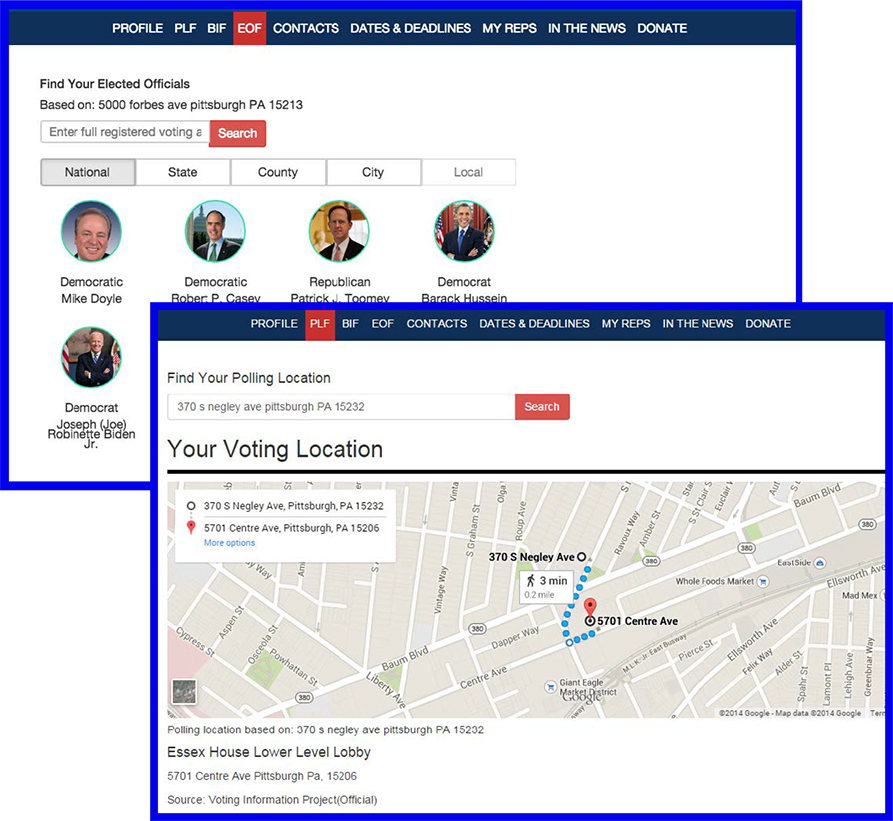

Working with the Overseas Vote initiative of the U.S. Vote Foundation, another team of Heinz College students created voting information widgets for the client’s Voter Account application. The widgets provide the voter with key election information regardless of their current physical location, meaning that an active duty servicewoman stationed in Kuwait could download the app, authenticate her identity and voting privileges, plug in her permanent address in California, and find out exactly what and who is on the ballot back home.

Screenshots of the widget interface

---

In 2014, U.S. voter turnout was at its lowest since World War II, and media outlets devote a lot of attention to the voting habits (or non-habits) of members of the “millennial” generation.

While millennials (roughly defined as people currently ages 18-35) have the lowest voter turnout of any age group domestically, representation is far worse for overseas voters. The Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) reported that only 4 percent of eligible overseas voters cast ballots in 2014, a shockingly low figure.

Dzieduszycka-Suinat suggests that many overseas voters don’t know their rights, and are not properly informed of their voting rights when they leave the country. Nor are they required to register with an embassy or consulate, making them difficult to track down.

Even among the registered overseas voters who requested a ballot in 2014, the FVAP report said less than 60 percent of them confirmed they “definitely voted.” This is despite the fact that, according to Dzieduszycka-Suinat, absentee voting is a simpler process for an overseas voter than it is for a domestic one.

While technology would help overseas voters stay more informed about (and possibly feel more connected to) American elections, this has clear upsides for domestic voters as well. The student deliverables to Overseas Vote included a polling location widget that uses Google Maps to guide the voter to his or her polling place, and the capability to communicate via social media features to maximize voter engagement, particularly among millennials.

The students took steps to ensure confidence that the information being transmitted via the widgets were correct for the user, such as multi-factor authentication and other security validations that would mitigate the risk of attacks that could deliberately misinform voters.

As an advocate for responsible voting, Bandes applauds the project, stating that it’s good for people to be able to obtain information in the modality they’re most comfortable with.

“People want to go to the polls informed about who really stands for what,” said Bandes. “They don’t want buyer’s remorse.”

The future of voting

In American life, there is arguably no asset more valuable than the people’s right to vote and make their voices heard. That principle has led some experts to insist that our voting systems should be accorded the same level of security as other critical infrastructure. While Internet voting may not plausible in the immediate future, that’s just one small piece of the puzzle. Until the technology catches up, Dzieduszycka-Suinat says that policy can start to close the gaps, such as automatically registering men and women in the armed services.

“You can see improvement in a lot of ways through reasonable, sensible reforms that don’t involve risking the integrity of the ballot.”

The first Capstone Project cited, titled “Online Voting System Prototype for Secure Scalable Voting,” was completed by Akash Gandotra, Kyle Hui, Yijie Qiu, Prabh Simran, and Amelia Xiao.

The Overseas Vote Foundation project was completed by Julian Brown, Ladan Khamnian, Pavan Kumar Sunder, and Chenlong Yang.